|

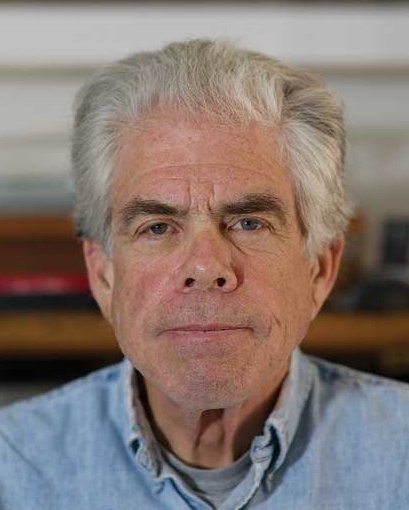

| Robert Allen Follett |

| Name: | Robert “Bob” Follett |

| Born: | March 8, 1943; Seattle, Washington |

| High School: |

Roosevelt High School 1961; Yonkers, New York Berkshire School, Sheffield, Massachusetts |

| College: | BA, University of Washington 1967; Seattle, Washington |

| College Activities: |

Publisher and Editor, Seagull Magazine Uncle Robert, a Weekly Humor Column, The Daily Varsity Bowling Team, Freshman and Sophomore |

| Military: |

Infantry Lieutenant, U.S. Army; served with the Seventh Infantry Division in Korea 1968 - 1969 |

| Currently Residing: | Oakland, California |

| Earlier Employment: | Marketing Support; Grubin, Horth & Lawless; S.F. V.P.; First Montgomery Corporation; S.F. Director of Marketing; Larry Smith & Co., Ltd.; S.F. Editor; The Rip Off Review of Western Culture; S.F. Real Estate Analyst; Fields, Grant & Co.; Palo Alto Associate; Keith Roberts & Associates; S.F. Partner; Heavy Duty Management (artist management); S.F. Weekly Comix Syndicate Manager; The Rip Off Press; S.F. Marketing Writer, U.S. Leasing Corp.; S.F. V.P.; William Hill Winery; Napa Proprietor; North Bay Business Computers; Napa |

| Most Recently Employed: | Information Architect; American President Lines; Oakland |

| Personal Web Sites: | Art and Life The Sole Proprietor's Journal Here in Oakland |

| Fooling Around: | The Ship of State Gazette Best To Question Here in Oakland There in Oakland A Dollar Down Occasionally Clever The Grateful Unwed Dreaming A Life Idiot Within Old Man With a Camera Said Then, Says Now Oakland Rider (www.oaklandrider.com) A Personal Sight (www.apersonalsight.com) A Fantasy Existence (www.afantasyexistence.com) |

| Hobbies: | Photography and this journal |

| Currently: | Retired |

I was born in Ballard, a Seattle Scandinavian immigrant district, delivered in Ballard hospital by an uncle who was a family primary care physician. My sister Jackie was born four years later in the same hospital delivered by our same uncle. All in all a pretty good way to start this living business. The family moved north of Seattle to Woodway Park south of the town of Edmonds when I was five. Lots of trees, not so many people. When I was twelve the family moved to Yonkers, New York, where there were lots of people and not so many trees. We lived comfortably, as my father managed the New York City office of an architectural firm known for designing regional shopping centers, some of which you've probably visited. The firm itself is best known for its design of the Seattle Space Needle. I returned to Seattle when I turned eighteen to attend the University of Washington. I founded Seagull when I was a sophomore, an off campus humor magazine with press runs that reached twelve thousand copies toward the end and was hawked by students around the campus and distributed on local newsstands. I don't recommend starting a magazine as a sophomore, not for the experience - it was great - but for the stress and the debt. This led to writing the “Uncle Robert” humor column for the University Daily for two years. In a sense this online journal is an extension of that old weekly column which, after all these years, is probably a sign I've never grown up. I entered the army in the summer of 1967 where my Fort Benning Infantry officer class was told we'd be spending the last year of our two year commitment in Vietnam. The balance of that first year after Benning was spent in a Ft. Lewis training company south of Seattle. Anyone remember an American spy ship named The Pueblo? The North Koreans captured it? Caused a stink? This happened just as I was due to be rotated to Vietnam and caused me to be diverted to Camp Casey, Korea, where I served as G-4 Plans and Operations Officer on the Seventh Division General Staff sitting in an office with a documents clerk (who did all the work) far from any fighting. I owe those guys on the Pueblo. A friend picked me up in his Volkswagen bus when I returned from Korea with the idea it was 1969, the world had gone psychedelic and we'd better head to San Miguel de Allende (north of Mexico City) to finish our respective novels, drop acid and drink. Which we did. We'd heard that Neil Cassady, former beat sidekick of Jack Kerouac (Cassady had been his model for Dean Moriarty in On The Road) and member in good standing of Ken Kesey's Merry Pranksters, the designated driver of the Pranksters“s psychedelic bus, had died of exposure passed out on railroad tracks near San Miguel de Allende after a night of heavy duty drugs and drinking. We felt it appropriate to pay homage to this hallowed ground for our own writing purposes. Had we not read Tom Wolf's The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test? Were we not setting out freed from the bonds of school, military service and gainful employment? Did my instigator and traveling companion Mr. Braggart not own a fabled Volkswagen Bus and did we not have the wherewithal to spend whatever number of months in Mexico that may be required to do things we had, then, only read about? Then again I'd wanted to see what Gilbert Shelton and Jack Jackson (Jaxon) were up to in San Francisco. Gilbert had been the editor of The Texas Ranger, generally acknowledged the best college humor magazine of its time and creator of the Wonder Wart Hog series of comic strips, many of which I ran in Seagull. I hadn't met Gilbert, but I'd corresponded with Jackson and gave him a call when we hit San Francisco on our way to Mexico. Jackson suggested we drop by The Family Dog headquarters (where he was the art director) and say hello, which we did, both of us learning that he, Gilbert, Dave Moriaty and Fred Todd had formed The Rip Off Press earlier that year by pooling $400 and buying a printing press to publish underground comix and “rip off” better royalties for their artists. Returning from Mexico to Seattle Mr. Baumgart dropped me off at a condemned building, part of a redevelopment project near San Francisco City Hall, at that time home of the Rip Off Press, and I became a resident of San Francisco. THE SEVENTIES. Grubin, Horth & Lawless Through a series of chance events, running into an old friend from school who happened to know Al in San Francisco, running into Al some days later on Sansome Street - “you up for lunch?” - and I, not having the price of lunch, responding: “I've had lunch, how about coffee?” Well, Al (my age) worked for a company that was looking for someone to do marketing support, “what was it you did in school again? Something about a magazine?” Grubin, Horth & Lawless, later Grubin, Horth & Lawless Properties, was a real estate syndication company with less than a dozen employees. It isn't necessary to know more than that, but if you're an ambitious youngster who wants to make a lot of money in life and have a judicious tongue, reasonable smarts and you're willing to put in a certain amount of effort, working for this kind of a company isn't a bad way to make it happen. My suitability for real estate syndication could be distilled from an answer I gave to Al when he once asked: if I could meet anyone in the world, talk with anyone in the world at say a party, who would that be? Well, how about a writer such as Kesey, Mailer or Hunter Thompson? Al thought for a minute and suggested maybe I was in the wrong business. Al, with an MBA, was thinking more along the lines of a Jack Welch, famous for making General Electric spark. Good advice, I suspect, or I wouldn't remember his question. Good advice that I might have followed, maybe, with the price of lunch in my pocket that day on Sansome Street. What did a “marketing support” person do in the investment business? Well, in a company as small as G. H.& L. you did many things that wouldn't be considered marketing support in a large corporation, but I was the guy who wrote, designed and arranged the printing of the offering documents that were used to sell their investments, wrote and designed the direct mail, wrote the investor letters - all marketing support - but also learned to run the numbers on potential investments: how they worked when they worked, how they didn't when they didn't. Mortgages and such. Sales organizations and investment advisors: what they did, how they did it, what it took to make them happy. I arranged to have my first investment document printed by Don Donahue, who ran a one man printing operation, Apex Novelties, and had been the publisher of the first issue of Robert Crumb's Zap comix before it was picked up by Berkeley's The Print Mint. Donahue charged half what G. H.& L. had then been paying (making them happy) and Don received maybe twice what he'd been accustomed to receiving (making him happy) and that, I must admit, was fun. And, I don't know, having your first effort printed by an underground comix publisher was definitely pushing the envelope, but stupid is how you learn, I guess. In retrospect. G. H. & L. was easily one of the better companies I worked for, my introduction to “real” life in the working world. The people were professional, gave me more than enough rope to hang myself and then came back time and again to cut that rope when I found myself hanging. I didn't belong in real estate or finance, my answer to Al's question pretty much settling the question, but the world was young, I was young and “what the hell”, I was living in San Francisco riding a cable car to work in the mornings. First Montgomery Corporation “What the hell” was First Montgomery Corporation, a company formed by William Hill and a group of fellow Stanford MBA graduates (with one lone Harvard MBA for balance) and me (included for, well, diversity) when we broke away from G. H. & L. to form a new kind of real estate syndication operation and set the world on fire. Setting the world on fire introduced me to what the real corporate world was about - talent, ambition, politics, seat of the pants business plans - none of which were in any sense negative other than I wasn't much cut out for any of it. I wasn't altogether ambitious, had no problem competing if the competition was in producing, say, a piece of writing, but I was useless when it came to laying my life out for goals I didn't hold or share. Perhaps the corporate version of “life in the suburbs”, the American Dream, something I've been fleeing since the age of twelve. Oh. The First Montgomery business model didn't work and that was too bad, it led to debts and such, but the others went on, from what I'm able to determine, to where they'd been planning (Stanford MBA's, from my observation, tend to be focused). I did some interesting writing and production (including photography) of brochures, coordinated an interesting ad campaign, an interesting and successful direct mail marketing program and raised money from people who eventually lost their entire investment when the company failed. Don't regret the experience, wouldn't want to repeat it, but that's life in the big city when you're just starting out. The Rip Off Review of Western Culture Dave Moriaty, one of the four founders of the Rip Off Press, wanted to start a magazine in the early seventies. He was a friend, he knew I'd done Seagull, an off campus humor magazine at the University of Washington, and he asked if I'd like to take a crack at editor. He'd have rather taken on the task himself, but he and Fred Todd were critical to keeping the Press itself afloat. Gilbert Shelton, another of the four founders, discussing the job with me one afternoon, described an editor he'd worked with in Austin, how he'd been good at doing off the wall promotional “events” and such to get the magazine noticed. A promoter I am not and he knew starting a magazine required some P. T. Barnum in the blood. Still, if I'd done things a little differently. If, if. Janie T. Gaynor, sent over to the Press by Paul Krassner, who was then publishing The Realist in San Francisco, had been working in getting that first issue together and between the both of us we got it started, selling through the Rip Off's comix distribution system and on newsstands in Austin. Ramsey Wiggins came up from Austin at Dave's invitation to write a column and help on the editorial side. Dave Sheridan was art director and we were able to bring together many of the best of the local poster and comix artists to help with the production. Kelly and Mouse, as I remember, were working on cover number four when we folded. Yes, I wasn't a promoter, but I should in retrospect have understood I had a free pass as editor to go out and meet people, many more than I did, to stir up interest in what was then an amazing San Francisco alternate publishing scene. Most of the underground newspapers were gone, true, but The Berkeley Barb was still publishing, Ramparts was still around, Francis Ford Coppola was publishing a weekly entertainment magazine, Rolling Stone in all its glory still had its offices down the street and I, clever I, was not out there nearly enough saying hello, how are you, what's up, what's happening? Some of the New York City writers associated with Saturday Night Live pitched in as did some of the writers in Austin. John Belushi sent a message through a writer he was interested. We did some good stuff. Still, those were good times. I wasn't doing much writing and what writing I was doing was, um, “strained”, but you can't have everything, now, can you? Starting a magazine? Probably not. Three issues: good times and excitement. Larry Smith & Company When they began building regional shopping centers in the United States in the early fifties, developers and retailers needed research on where to build their stores - how many people were in the area, how much money did they have, what kinds of things were they likely to buy? - and Larry Smith & Company began by providing that analysis with the planning of Northgate, the first American regional shopping center, built north of Seattle. I was hired as their marketing director. Now, First Montgomery Corporation was populated, as I mentioned, by some dozen MBA's from Stanford (and Harvard) and they were the real deal, the wave of the corporate future. But they were also my age, just starting out and approachable, so working with them wasn't all that uncomfortable. Stressful sometimes, you'd get bounced about, but you could operate reasonably comfortably with them and occasionally let your hair down. Larry Smith & Company, a small consulting company that had in the last year moved its main office from New York City to San Francisco, was owned and run by an older group who'd been around the block in their corner of the business world and I, young wet behind the ears I, had been hired partly because of my raising investment capital background. So I was uncomfortable. I wasn't sure where this was going and felt I needed to fake it until I found out. The Larry Smith & Co. president, Everett Steichen, who'd been with the company since graduating with a doctorate in Economics from the University of Washington - consulting of this kind at its core seemed more professorial than corporate - I'd met through my father and we'd been getting together for lunch now and again over the last year while I was at First Montgomery. We got along fine, but he was then wrestling with running a consulting company that was going through a consulting market revolution where small specialized operations like Larry Smith were failing, the future being in much larger one stop shopping operations that provided a wide range of services to very large clients and my “investment background” was not of a kind that could help. Not that I was particularly aware of any of this at the time. Still, I managed their computer contract with a mainframe house, my first connection to I. T., not that it was in any way extensive or complex, oversaw the production of another company brochure and learned some things about store analysis from people who knew what they were doing. An odd chapter that lasted less than a year. Fields, Grant & Co. This one, well, another interesting interlude. They managed people's money during a time when the market was in the tank, one of the few investment managers who'd made the right moves in taking their clients money out of the market before the crash and, as part of their operation, kept track their clients real estate investments. Younger guys, again, many of them Stanford MBA's including Randy Fields, very ambitious, very focused. What you want in the way of people who manage your money. I found myself doing interesting things. Writing the quarterly correspondence with the real estate investors, traveling to do due diligence on cotton farms in the middle of the Arizona desert, seeking out information on the robbery of a grapefruit crop located at the tip of Texas, negotiating with apartment house developers who's operations were having problems, putting together a partnership to solve a particular client's tax deferral needs. Randy, by the way, a bachelor when I worked for him (I worked for William Hill, who worked for him), later married a young woman he'd met at the Denver airport. It turned out she was good with cookies and Randy was good with financing startups. Cookie startups. Mrs. Fields Cookies. But that's a later chapter I know nothing about. Heavy Duty Management Ah, yes. One learns after a while, when you're in the investment business and it turns out you're not cut out to be in the investment business, maybe not in any business, to try other avenues for paying the rent and staying out of trouble. And what better way than rock and roll? ...more to come Keith Roberts & Associates Keith, a Harvard and Harvard Law School Graduate, had been staff counsel for Fields, Grant and Company during my brief tenure and had decided to set out starting a company of his own. In the investment business you spend quite a bit of time working with lawyers: outside counsel, inside counsel, investors' lawyers, broker's lawyers. Lawyers and lawyers. Keith was one of the more interesting (I have many interesting lawyers in my family, nothing against lawyers. I'd have become one and lived happily ever after had my mind been wired differently.) starting as a Nader's Raider in Washington, active in the environmental movement, as were many of the young MBA's, by the way, participating in what were then the “liberal concerns” of the time. I was naive and wrong in thinking MBA inevitably meant Republican. Perhaps a conceit of my New York days or not factoring in the reality of the draft. This was the early seventies, the anti-Vietnam war period, the beginnings of the environmental movement and civil rights. Oh, and Keith's brother financed Woodstock. The idea was to raise capital for The Preservation Group to buy old landmark San Francisco buildings and restore them using local construction people and some of the then interesting house painters who were doing elaborate multi-color Victorians projects, this in conjunction with a local architect who'd founded the group. Keith thought I could make a contribution. As an associate. He was wrong, but he was nice to be wrong and at least his vision in preservation real estate turned out well. What to say? I was not a happy camper, had no focus, no interest in what I was doing, although, from the things we were doing, you'd have to ask why? We did buy and successfully renovate a number of San Francisco landmarks including the Abner Phelps House and the Mish House, the Abner Phelps thought to be the oldest still standing residence in San Francisco. Originally said to have been shipped in pieces around the horn from New Orleans and assembled in the 1850's but later, after detailed inspection, learned to have been built locally of local materials. I mean really. What was not to like? ...more to come. |

|